In the old days it was a paper town. Every one who lived in it had sentimental emotions towards the rows of red brick factories. Men and woman spent lifetimes in those mills, and there were three shifts in the boom days and the factory lights burned deep into the black nights. The factories were built between the first and second level canals, and the race of water flowing with gravity drove the huge turbines. The mill workers raised families out of those mills, and there was a proudness in their strides, knowing they had made some of the world’s finest papers.

Then one year there was no logs to make paper. Many of the stands of timber had been cut bare by the wood cutters, and the orders for paper went to other parts of the world. The freight trains pulled in on the steel tracks, and the last of all the huge rolls of paper were loaded in box cars. The red brick factory buildings had all their machinery unbolted from the hardwood floors and hoisted on flatbeds trains by the men who had worked in the mills. The line of those trains carried everything on their iron beds that had made the mill the paper mill; and left behind were the empty factories of red brick where the janitors had stayed on for a while to sort out the last and sweep them down, until they were given their walking papers and the doors were locked, with only the slanted rays of sun now through the window glass as company.

Time had marched. Thirty years later the wooden doors were still locked. Fifty years later time had buried almost all of the mill workers, and even a lot of the old stories had died in the webs of time. Father Time never mourned for any of the dead, for his brazen heart had never known love, and he pushed forward through the perpetual striking of metallic hands.

The spring rains that year had sprouted new stock wood on the vines and there was a sudden burst of buds, and the green shoots under the summer sun and the fall rains sent canes climbing the face of red bricks on the old factory. The shoots raced against time, and soon the tendrils had creeped over the masonry and sill works. Even the plate glass where the faces of mill workers once gazed upon the city limits, were engulfed by the marching of time.

Many years had passed, and never once was this figure stricken by the hands of curiosity, and venture past the old canals and red brick factories that still stood square and plumb on their foundations.

But then one year the snows had melted, and the spring showers returned to the old mills. For what reason the bade arrived for investigation, I can not recall and would only be telling stories to provide a solid answer. But one grey morning in the cusp of spring tides, my truck tires were humming past the old canals, the water blue-black in the breaking of dawn, and the red brick soldier rows of factories on the horizon. Good fortune had fallen in place, and thinking ahead of time, both of my film cameras has been placed in canvas satchels. The proper speed of film had been procured for the zenith of dove grey clouds. A cheap pair of reading had been taken on the photography street shoot, for feebleness of the eyes made a tough game of setting stops on a manual camera. Shooting film takes preparation and knowing the proper setting in the values of light.

This particular street had never been explored. It was known to be the rough side of town. Precaution is needed after the fall of night. Prudent men practice these rules. Rough characters and street gangs were known to lurk there. But now in the cracks of dawn, the ghetto was sleeping sound. Not a soul was stirring, and my tires rolled over their stomping grounds.

I’d darted around the corner at the old bakery, and crept down that particular street in the pickup truck … and there was the pronounced work of Father Time — the face of the red brick factory had been engulfed with vines!

A wild maze of vines. Stunned with the visual effects, the gear shift was jockeyed into the neutral position, and with the motor still purring this photographer sprung from the cab and down on the dead street. My fancy grew wild with infatuation. This was rare subject matter. The vines had covered the red door, and the brick arch had been swarmed with canes. Some vines were bigger than a man’s wrist. Further advance revealed a brass door knob. The last of the factory workers had walked through that red door when the factory closed.

Everything was clear in my brain. Artists see those things. The title of that composition leaped from behind the red door smothered with vines — The Recluse.

Threads of orange sun were peeking on the skyline. The golden hour was here. Film worked well in these light conditions. The buds on the vines were swollen. Time was pinched. Soon the buds would sprout into green leaves … and cover the composition.

Both cameras were loaded with film. I braced in the pickup bed for effects. My elbow rested on the truck’s cab. Trust was placed in my Mamiya 645 Pro. A complete roll of colored film went through the black box. The second camera was pulled from the canvas satchel — my Nikon F4. Perhaps the best camera for a street shootout. The shutter clicked in the still of daybreak. My trigger finger pressed out a few more. We call that insurance in the film world.

Film developing showed a winner. The Nikon F4 had come through in the pinch. The other black box had provided poor results.

Roger in the dark room loved the image. I’d been after him for years now to go on the wagon; but he could not shake the need for alcoholic beverages. He pulled a pint a peach brandy from his pocket, and suggested a toast to the fine image — The Recluse. We both pulled from the bottle. Roger killed it and the booze brought him into a coughing jag — “Ugh! ugh! ugh!—ugh!”

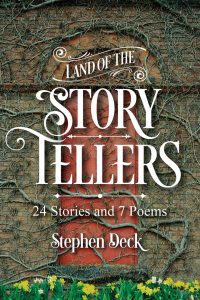

Sometimes all the work brings perfection. The film had done its job. The image of The Recluse was born. Right there on that particular street at the old red brick factory. Years later, that image would serve as the backdrop for my beautiful book cover — Land of The Story Tellers.

Many years had passed before I went back to the old factory. It was Christmas Eve and a light dusting had fallen over the city limits. I’d gone to the chapel to light candles for the dead in my family. Three candles that flickered in the shadows.

Then I advanced to the old red brick factory. Where time had buried all the old factory workers. The dusted snow covered the stoop, and the red door showed vivid colors in the flat light. A lone set of footprints went under the red door. Shoe marks in the snow.

True! — very, very dreadfully nervous I was. But even yet in the grips of winter I kept still. Scarcely breathing. Tiny puffs of steam rose from my lungs. A light tap was procured on the red door. There was no reply. A light wind came rustling through the vines. From my pocket a silver dollar was drawn, and slipped under the red door. Time waits for nobody. She buried all the factory workers, and her heart they say is cold as the dead of winter.

In pace requiescat!

— Stephen Deck wrote this story in a single sitting riveted into the black night, on June 18th, 2024. The treat of the night while humped over the keyboards, was the fireflies who kissed my window and blinked into the summer night.